Environmental scientists have spent the last few years sounding the alarm on the growing single-use plastic waste problem plaguing landfills. Consumer-based products like plastic bags, straws and water bottles are often named as culprits, but inside laboratories across the country, researchers are faced with their own single-use plastic dilemma—pipettes.

A single lab can discard an average of 36,000 pipettes each year. Georgia Tech is addressing the problem with a solution that focuses on reuse of this critical lab tool through its Tip Cycle program.

“This does not come from the traditional recycling method; the tips are not manipulated or changed,” says Adam Fallah, project manager for the program. “It’s more reuse versus recycle. The life cycle of the pipette is lengthened.”

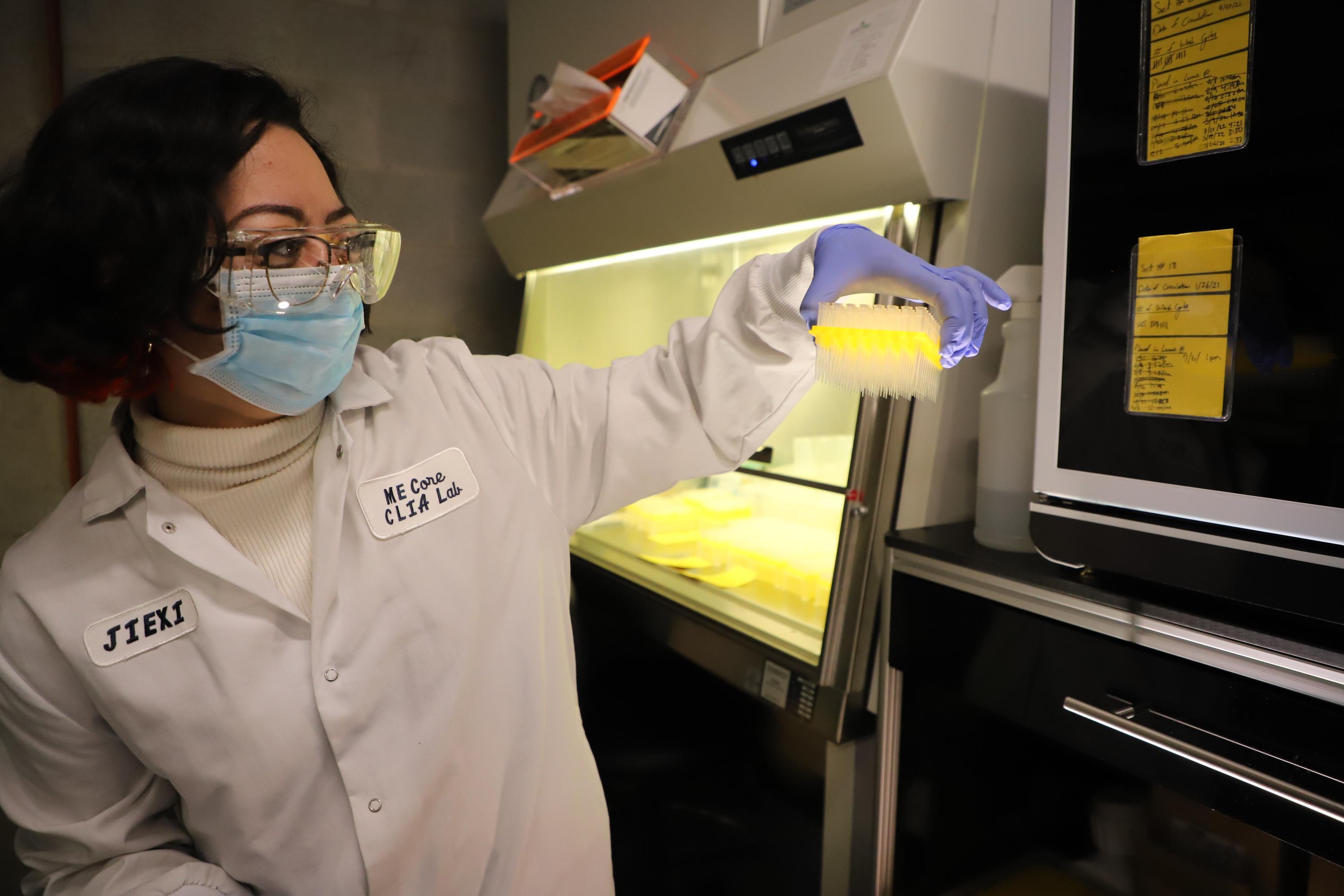

Housed in the Molecular Evolution Core (MEC) of the Parker H. Petit Institute for Bioengineering and Biosciences (IBB), the Tip Cycle program is capable of washing unfiltered pipettes to allow for multiple uses before discarding them.

MEC purchased the pipette washing technology from laboratory equipment supplier Grenova in 2020.

Typically, a research lab will purchase hundreds of boxes of pipettes, use them once, and then throw them away. This cycling program eliminates that waste and cost by reusing the pipettes.

So far, Fallah says the team has washed more than 746,000 pipettes in the last year, saving the equivalent of five tons of plastic going to waste.

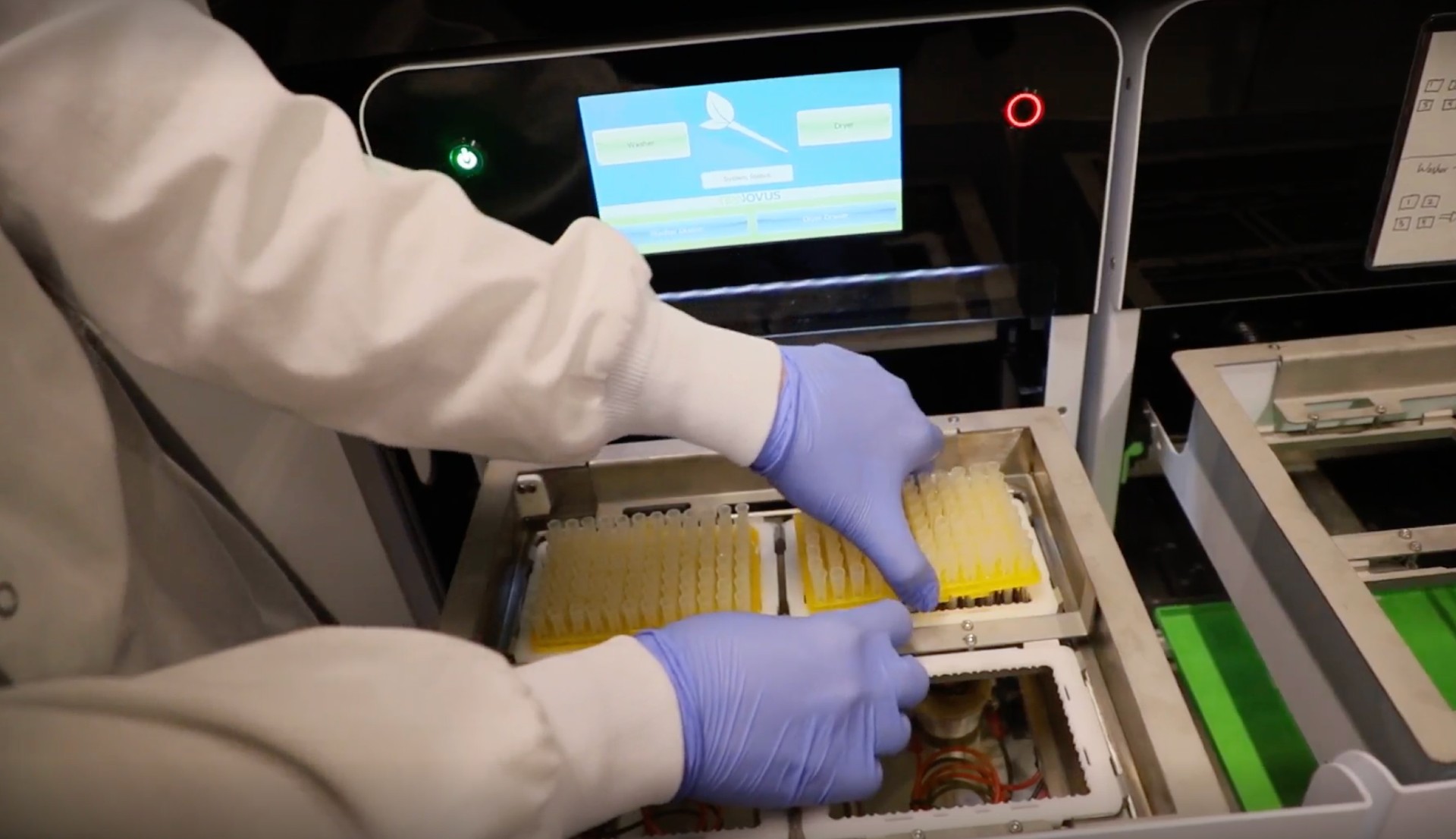

Grenova’s technology is similar to a laundry washer and dryer—used pipettes are set in a tray and loaded into a washer to go through several cycles before being dried, repackaged, and sent back to a lab. The cycles include multiple-high heat rinses, UV sterilization, and sonification, which uses sonic waves to disturb any residue, like proteins, in the pipette tips.

Fallah says he uses an in-house cleaning solution and can customize it with a 5% bleaching solution if requested by a lab.

The full processing time for four boxes of tips is two hours and eight minutes. Roughly every 25-30 minutes another round of cycling begins as the boxes of tips are rotated out. Pipettes are returned to clients within 2 to 3 days.

“We can pump out 40 boxes in 5 to 6 hours a day,” says Helya Taghian, operations manager and a fourth-year student in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory University. “We do 60 to 70 wash cycles of 200 to 300 boxes of tips a month. It would be a money sink if you bought that many tips…you have to be a pretty big lab to go through that many tips.”

Like the Sanger Sequencing Initiative, the Tip Cycle program was conceptualized at the height of Covid-19. Georgia Tech’s Covid-19 testing program was on the brink of being forced to halt the processing of Covid-19 samples as it faced a dire pipette supply shortage.

Principal research scientists Mike Shannon and Mike Farrell, along with Regents researcher and MEC technical director Anton Bryksin, called an emergency meeting to come up with a solution.

Bryksin devised an unconventional idea of washing the tips, a risky move given the sensitivity of qPCR techniques that can detect even a single molecule of RNA/DNA. Washing all the tips together also posed the potential for spreading contamination rather than eliminating it.

The Tip Cycle program garnered support from IBB and its assistant director, Michelle Wong, who recognized the potential for the project to help the university achieve its environmental sustainability goals.

Bryksin spearheaded the design of the program’s validation protocols, while Fallah took charge of implementing and organizing a student team to support the effort. The team encountered numerous hurdles in perfecting the washing process to ensure the tips were completely free of contamination, all while validating the washing protocol to maintain the accuracy of the qPCR results.

Bryksin says the program's initial success was nothing short of remarkable. It not only allowed the testing laboratory to continue processing COVID-19 samples, but also provided an environmentally conscious alternative that substantially reduced the amount of plastic waste generated by the lab.

As a result, the Institute recognized the potential of the Tip Cycle program and provided funding for its further development and enhancement.

At the same time, Taghian was one of several students supporting the Covid-19 surveillance testing program.

“There was a dark corner in the lab and my curiosity sent me there to see what Adam was doing,” she recalls. Initially, she spent much of her time helping Fallah rack pipette tips to be placed in the machine.

Eventually, she teamed up with Fallah to take the lead on developing an operational process for the program.

“I learned a lot of things about optimization,” Taghian says. “I was having a lot of fun and there was a lot of innovation in it.”

Taghian worked with fellow biomedical engineering student and program manager of the Sanger Sequencing Initiative, Nicole Diaz, to hire students for the Tip Cycle program.

Other aspects of the program began to fall in place. Data management charts and a workflow management board helped to keep operations running optimally. The duo also hired an industrial design major to create branding and a website.

“We want this to be educational,” Taghian says. “No matter what your major you can gain industry experience while doing your research. You’re dealing with vendors and actual instruments in a business environment. At the same time, your major has a place to shine.”

Scaling Up for the Future

Currently, the Sanger Sequencing Initiative and labs run by Associate Professor Kirill Lobachev and Professor M.G. Finn in the College of Sciences utilize the Tip Cycling program. Fallah says he is in talks to bring on another lab and looks to partner with teaching labs in the School of Biological Sciences to educate more students about single-use plastics in laboratories.

Fallah also wants to devise a plan to wash pipette tip plates, as well as find other ways to reuse the plastic inserts and boxes the pipettes are delivered in. The hope is to get as close to zero-waste with the program.

“Very few research institutions have a core facility with in-house services and in-house researchers assisting labs across campus,” Taghian says. “An environment exists on our campus where students can get an opportunity to explore an industry field without going off campus

Fallah says researchers are often “creatures of habit” and may gawk at the idea of reusing pipettes over fears of cross-contamination. But he stands by the efficacy of tip cycling as a sustainable way to manage pipette use and alleviate supply chain issues.

“We’re in a prime position right now to be a pioneer and change the future of labs.”

To register a lab for the program, or be hired as a student work, visit the Tip Cycle program website.