Your DNA is continually damaged by sources both inside and outside your body. One especially severe form of damage called a double-strand break involves the severing of both strands of the DNA double helix.

Double-strand breaks are among the most difficult forms of DNA damage for cells to repair because they disrupt the continuity of DNA and leave no intact template to base new strands on. If misrepaired, these breaks can lead to other mutations that make the genome unstable and increase the risk of many diseases, including cancer, neurodegeneration and immunodeficiency.

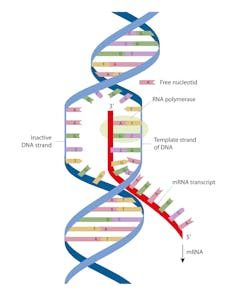

Cells primarily repair double-strand breaks by either rejoining the broken DNA ends or by using another DNA molecule as a template for repair. However, my team and I discovered that RNA, a type of genetic material best known for its role in making proteins, surprisingly plays a key role in facilitating the repair of these harmful breaks.

These insights could not only pave the way for new treatment strategies for genetic disorders, cancer and neurodegenerative diseases, but also enhance gene-editing technologies.

Sealing a Knowledge Gap in DNA Repair

I have spent the past two decades investigating the relationship between RNA and DNA in order to understand how cells maintain genome integrity and how these mechanisms could be harnessed for genetic engineering.

A long-standing question in the field has been whether RNA in cells helps keep the genome stable beyond acting as a copy of DNA in the process of making proteins and a regulator of gene expression. Studying how RNA might do this has been especially difficult due to its similarity to DNA and how fast it degrades. It’s also technically challenging to tell whether the RNA is directly working to repair DNA or indirectly regulating the process. Traditional models and tools for studying DNA repair have for the most part focused on proteins and DNA, leaving RNA’s potential contributions largely unexplored.

My team and I were curious about whether RNA might actively participate in fixing double-strand breaks as a first line of defense. To explore this, we used the gene-editing tool CRISPR-Cas9 to make breaks at specific spots in the DNA of human and yeast cells. We then analyzed how RNA influences various aspects of the repair process, including efficiency and outcomes.

We found that RNA can actively guide the repair process of double-strand breaks. It does this by binding to broken DNA ends, helping align sequences of DNA on a matching strand that isn’t broken. It can also seal gaps or remove mismatched segments, further influencing whether and how the original sequence is restored.

Additionally, we found that RNA aids in double-strand break repair in both yeast and human cells, suggesting that its role in DNA repair is evolutionary conserved across species. Notably, even low levels of RNA were sufficient to influence the efficiency and outcome of repair, pointing to its broad and previously unrecognized function in maintaining genome stability.

RNA in Control

By uncovering RNA’s previously unknown function to repair DNA damage, our findings show how RNA may directly contribute to the stability and evolution of the genome. It’s not merely a passive messenger, but an active participant in genome maintenance.

These insights could help researchers develop new ways to target the genomic instability that underlies many diseases, including cancer and neurodegeneration. Traditionally, treatments and gene-editing tools have focused almost exclusively on DNA or proteins. Our findings suggest that modifying RNA in different ways could also influence how cells respond to DNA damage. For example, researchers could design RNA-based therapies to enhance the repair of harmful breaks that could cause cancer, or selectively disrupt DNA break repair in cancer cells to help kill them.

In addition, these findings could improve the precision of gene-editing technologies like CRISPR by accounting for interactions between RNA and DNA at the site of the cut. This could reduce off-target effects and increase editing precision, ultimately contributing to the development of safer and more effective gene therapies.

There are still many unanswered questions about how RNA interacts with DNA in the repair process. The evolutionary role that RNA plays in maintaining genome stability is also unclear. But one thing is certain: RNA is no longer just a messenger, it is a molecule with a direct hand in DNA repair, rewriting what researchers know about how cells safeguard their genetic code.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.